Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

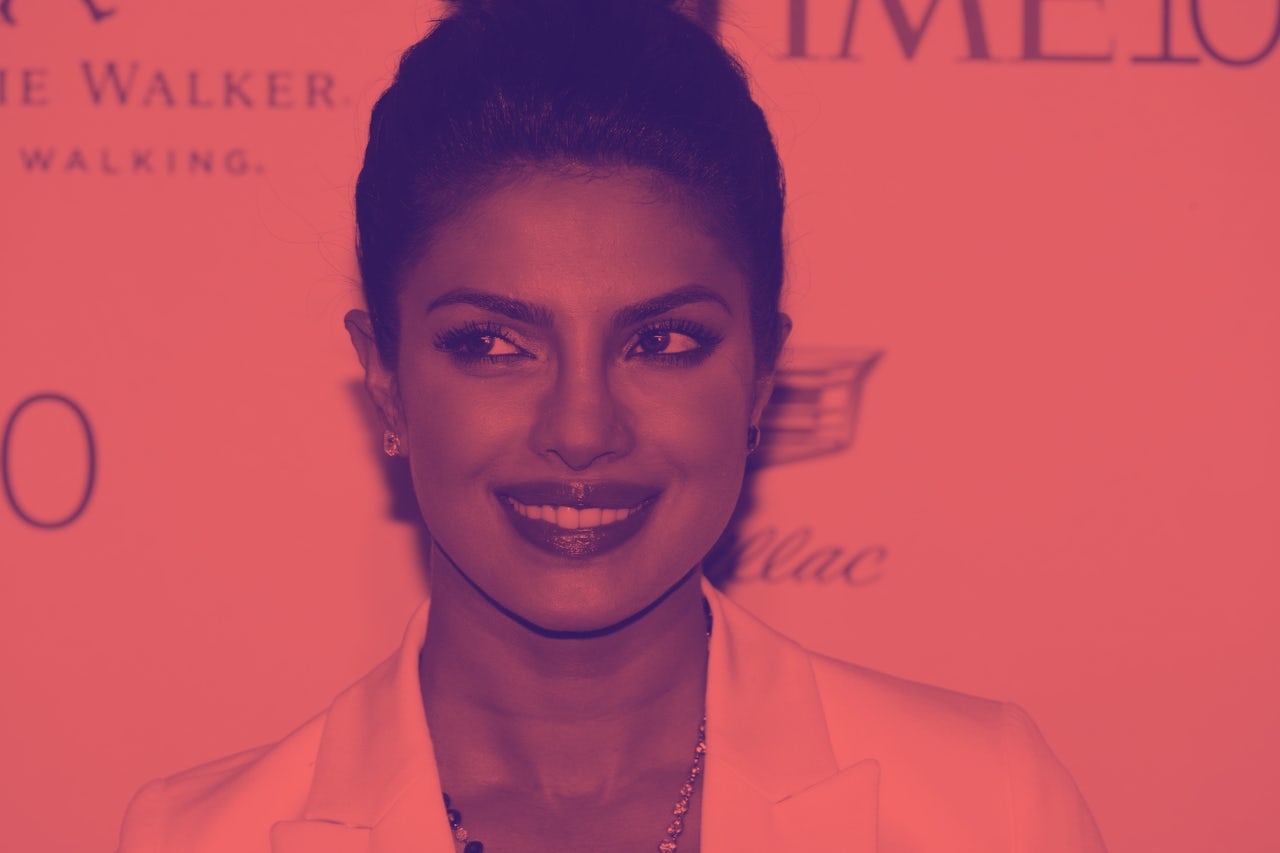

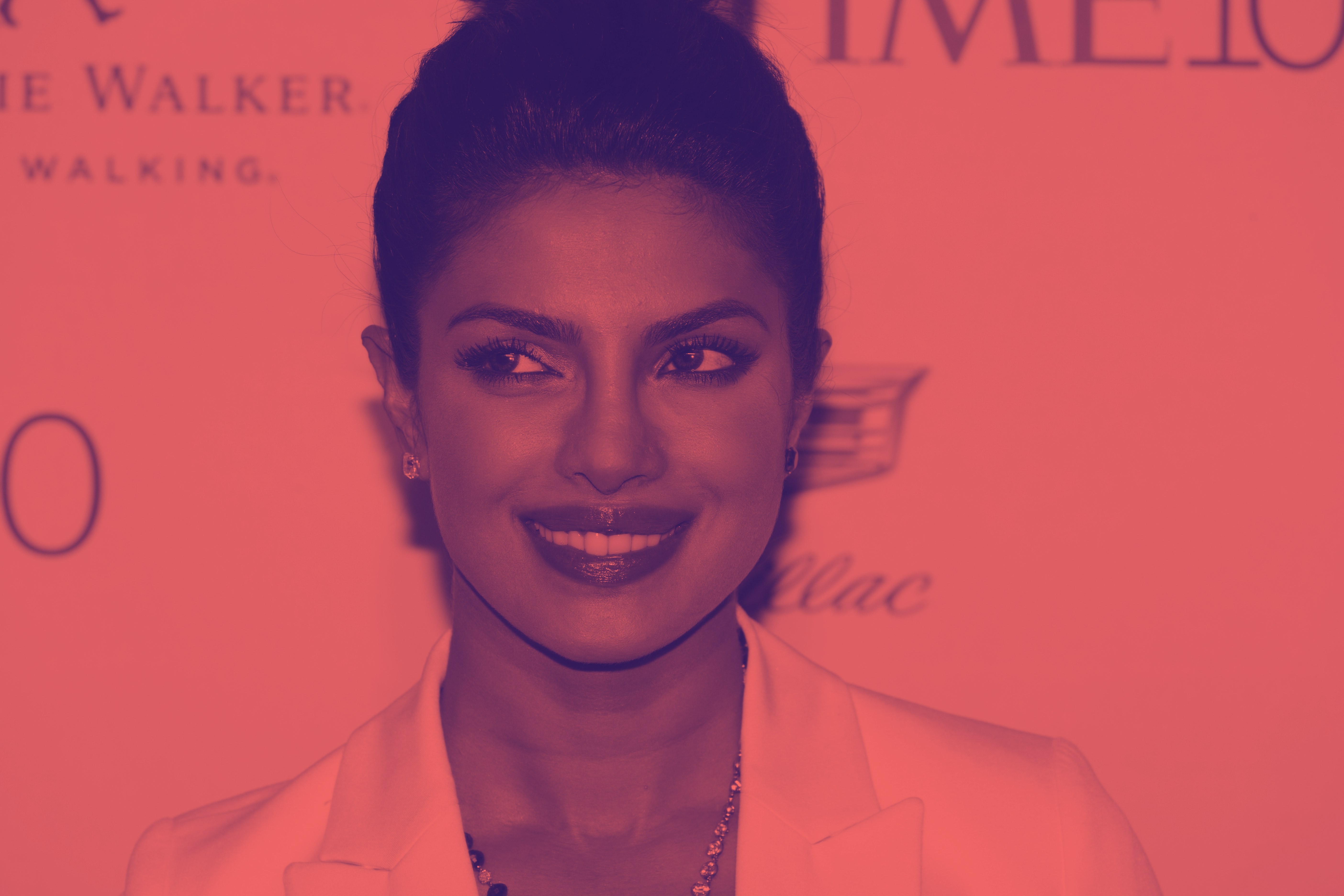

The press, Indian and American alike, tends to describe Priyanka Chopra in the language of global domination. “As I see it, this is not a career,” Indian film journalist Anupama Chopra (no relation) told Chopra in an interview last September while listing the actress’ recent achievements, from production credits to the renewal of the third season of ABC’s Quantico. “This is a world domination.” Chopra, in response, laughed: “I like the way you put that.” It was a self-effacing remark, but something about it felt subversive, too, as if she was knowingly colonizing a world she knows that usually keeps women like her on the margins.

Barring an unforeseen catastrophe, Chopra seems positioned to be Indian cinema’s first true crossover star, following a long career. I first saw her in a Bollywood film she’d made in 2004 called Mujhse Shaadi Karoge (Will You Marry Me?), where she’s entangled in an aggressively unexciting love triangle. (I didn’t think much of her in it, though I was also 12 years old.) I’ve witnessed her climbing through Bollywood in the early aughts, winning a National Film Award (a highly prestigious award given by the Indian government, with the cultural weight of an Oscar), starring as a Guess girl, and briefly pursuing a music career in the United States. She has been acting for the better part of fifteen years, though I’d wager that many Americans probably hadn’t seen her before Quantico, the ABC primetime show she’s headlined since 2015. (Quantico is, notably, the first primetime show in American history to star a South Asian actor in the lead.)

The ascent to fame within America has rarely been as smooth for other Indian actresses, making her rise seem somewhat singular. In the summer of 2004, Aishwarya Rai, perhaps still famously known as the world’s most beautiful woman, made her debut in English-language cinema with Bride & Prejudice. It’d been fashioned in the likeness of the Austen novel its title references, and it was meant to signal her arrival in the context of global cinema. It was a considerably more hopeful and naive era than the one we live in today. Much of India and its diaspora believed Rai — a classic, gobsmacking beauty with gunmetal blue eyes — would be Indian cinema’s first crossover star. (Rai had won Miss World in 1994 at the beginning of a spectacular run in which India won the title four times over six years.)

But Bride & Prejudice barely registered, and Rai never became as big a star within the States as she continues to be in India. I guess it’s metaphorically apt that Rai’s failings presaged the eventual successes of Chopra, who won Miss World at the tailend of that spectacularly lucky period. When there’s nobody around who looks like you, you end up paving the way for whoever comes next, even if that’s not what you set out to do.

I’ve had quite a bit of ambivalence about Chopra in recent years. I am suspicious of the appeal she holds, or, rather, to whom she appeals. As the product of the pageant world and Bollywood, she can so easily embody a fantasy of bland diversity and non-threatening exoticism in a Western context. These sensibilities have been reflected in her art, or, better put, her products. Take “Exotic,” her Pitbull-featuring single released during her courtship of a music career in 2013. The song’s colonial teases were right there in the bland, distinction-less chorus: “I’m feeling so exotic,” she sings, “Yeah right now / I’m hotter than the Tropics”. Listening to it even now, I wonder who her imagined audience was, or what pressures she was working under to make her sing without personality or imagination. (The song, predictably, made little dent in America.)

Quantico, on paper, didn’t inspire much confidence when I first heard about it, either. Here was Chopra playing a woman named Alex Parrish, who happens to be an FBI recruit. (Her name gives the impression that she’s deracialized, though, Parrish is, in fact, biracial, with a white American father and Indian-born mother, hence the surname.) Primetime television’s first South Asian lead has a name you could very well believe belongs to a white woman, one who devotes her life’s work to the state’s carceral apparatus.

For these reasons, my head tells me I should know better than to respond to Chopra in Quantico, but I’m afraid my heart is fickle and dumb. Watching her on American primetime television, a context so far removed from Indian cinema, was a seismically disorienting experience, because Chopra isn’t working on paper in this show. She’s somehow given this character such flesh and blood, which I didn’t realize was capable of her. Some alchemy of her presence, her voice, and her carriage made me respond to her on screen in a way I hadn’t before. The natural register of Chopra’s voice is low and gravelly, and she speaks in a beautifully tempered accent that exists somewhere between Mumbai and Massachusetts. She gets by on her charisma, and Quantico asks little more of her than that, but that charisma is so robust that it’s enough.

Watching Chopra on Quantico forced me to reevaluate and question everything I’d assumed about her abilities before. American television was a change of pace that suited her, I figured, giving her talents the proper form and care that popular Indian cinema never could. It’s pretty seldom that someone bubbles to the top of her industry without having any talent to show for it, after all, and Quantico reminded me of this rudimentary truth.

And then she made her Hollywood debut in Baywatch, a real slog of a blockbuster, where she did her best to make an impossible character — a drug dealer who also happens to own the beachfront property where the film’s principals work — seem sentient. She tries to inflect throwaway phrases with guile (“I’m not a Bond villain — well, yet,” she remarks in one scene), and it half-works. You see her grasping for gravitas where there’s little to be found, even though villainy doesn’t quite suit her. It’s a little sad; I worry that this is all that American cinema can offer her, supporting roles in negligible blockbusters. America and India are united, it seems, in their ability to create garbage movies. It’s heartening to know that Chopra has gotten to a point where these movies don’t deserve her.

It’s no secret that South Asian stars are rare specimens in American pop culture. Paucity begets desperation, and a cynical desire for us to champion these imperfect idols, if only so that the generation that succeeds ours has icons who share their skin tone, regardless of the politics they embody or espouse. This creates, within South Asian circles, a lazy pressure to root for figures like Chopra simply because of shared cultural backgrounds, in spite of any misgivings one may have about them. In Chopra’s case, I’ve come around to her rather cautiously; you could say it’s a reluctant embrace. My initial concerns about her still apply, namely that she’s willingly indulged a fantasy of a particular strain of liberalism that champions diversity in a decorative manner. This is the scaffolding on which she’s built her stardom.

I have no idea what Chopra will do next, which is why she excites me and worries me in equal measure. She has shown herself capable of being a fine, disciplined actress. I was bowled over by her in Bajirao Mastani, a three-hour elephant of an historical epic. It is a film of such excess that you’ve really got to scrounge for any signs of humanity, but you’ll find it in Chopra, who plays the scorned first wife of an 18th century Indian war general. I remember two elements about the movie months after seeing it: the songs, and the anguished look in Chopra’s eyes when she tells her husband he has broken her heart.

I didn’t know she was capable of expressing this kind of private tragedy. When an actor’s good, she can foster a sense of fierce identification. I saw her and was moved, because I felt like I’d known her my whole life.