Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

Last summer, I got really excited about a story that had it all: miraculous cures, area cannibals, Florida, and Enya. A noise complaint had been made in Miami, drawing police to a cluttered basement from which Enya’s New Age banger “Only Time” could be heard thundering. Inside, they encountered three cannibals sitting in a circle on the floor. The trio were ritualistically chanting in between bites of human flesh, which they believed to cure diabetes and depression.

If the picture sounds a little phony, that’s because it was technically fake. The neighborhood in question, a very Stravinskian “Vernal Heights,” didn’t even exist; the story was broken by the now-defunct satirical site Miami Gazette. But I say technically, because when it comes to Enya, I’m prepared to believe anything about her and the way people use her music to tap into another world. We know so little about her; she never tours and grants interviews so rarely that details are few and far between. Everyone has a vague idea of Enya, an amorphous entity that hovers in your peripheral cultural vision. She is like a sentient wind chime, all around us and always out of reach.

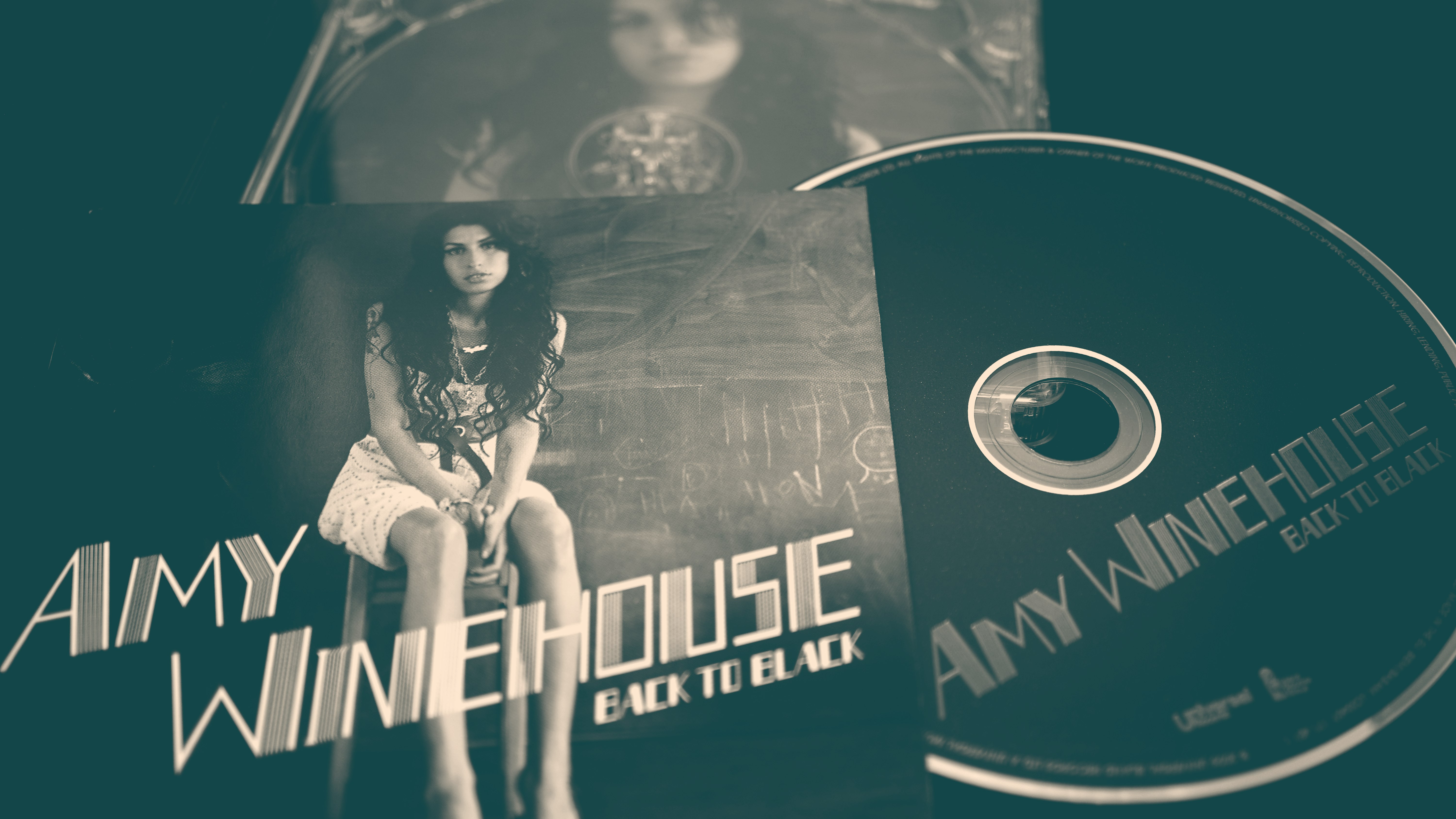

Born Eithne Pádraigín Ní Bhraonáin, Enya began her career by singing backup vocals and playing keyboards in the family folk band, appropriately named Clannad, before branching off on her own. After her demo tape gained some traction, the BBC invited her to soundtrack their six-part miniseries The Celts, a selection of which became her self-titled debut album. It charted respectably, but it wasn’t until the 1988 release of her second album Watermark that her global domination began. In late 2001, just as she was slated to appear all over the Lord of the Rings soundtrack, the newly-released “Only Time” was picked up by broadcast media as the go-to anthem in the wake of 9/11. To date, its parent album A Day Without Rain remains the bestselling New Age album of all time.

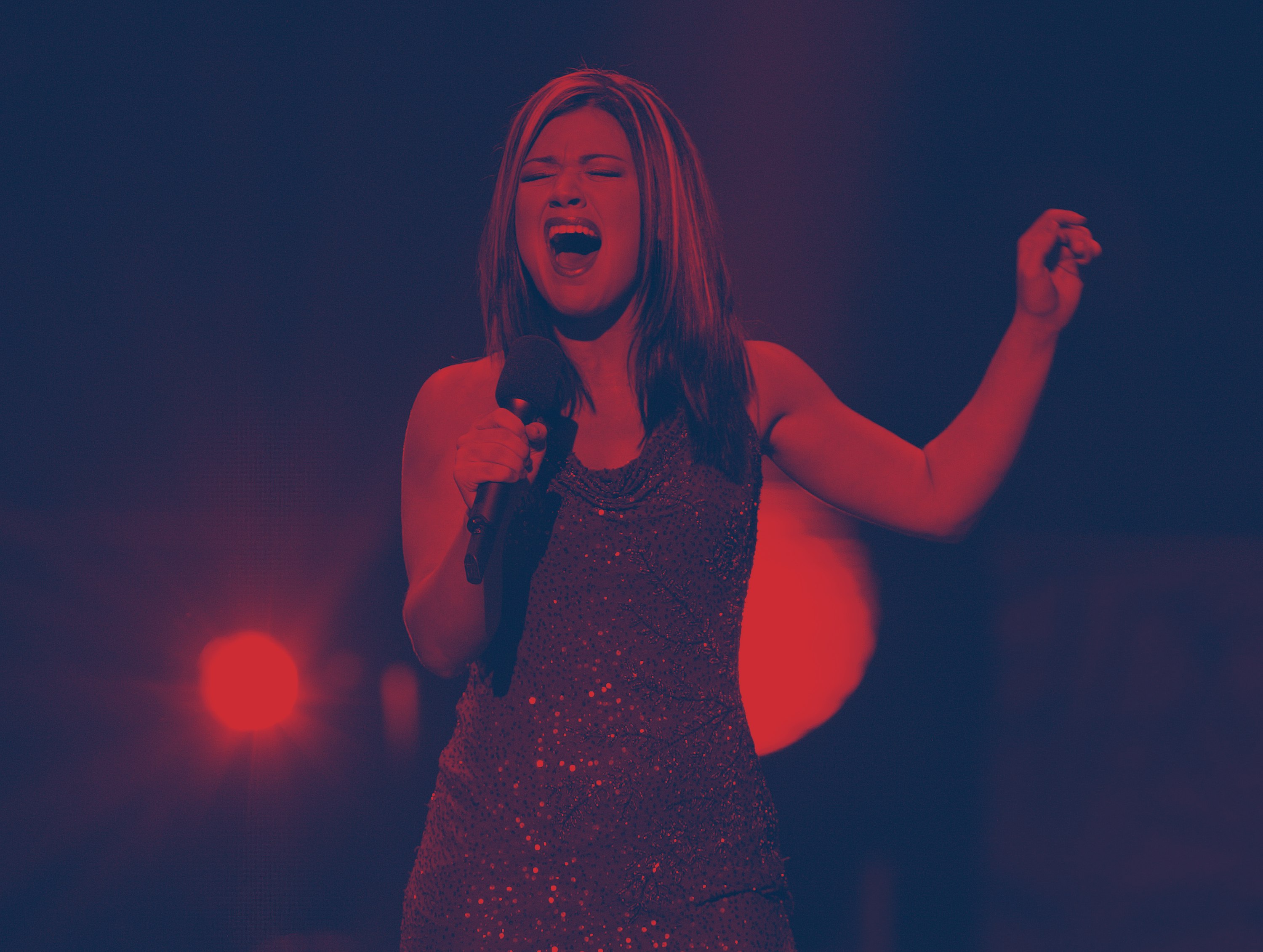

Over three decades, her music — or more specifically, the idea of her music in all its tinkling, ethereal glory — has so thoroughly permeated the world that it arrives in unexpected forms: as elevator muzak, or piped into the waiting room at the dentist’s, or soundtracking some blockbuster fantasy MMORPG. But sometimes you hear it as it was meant to be heard — a sonic mise-en-abyme of strings, shimmery bits and a millefeuille of vocal tracks — and it’s hard not to fall in love. She sings in ten languages, two of which are made up. My own introduction to Enya came upon seeing a Vine of a basset hound head, rippling its disembodied way through a field of corn to the tune of “Only Time.” I had grown up playing music in orchestras as well as in ska and riot grrrl bands — the ‘90s arrived in Dubai only in the early 2000s — with the end goal of a conservatory and a performance degree. In New York, I worked at my college radio station, listening to new bands took up much of my time. But when I stopped playing, I essentially stopped listening to music, and didn’t start again until that fateful Vine encounter.

I don’t know how long I spent looping “Only Time,” though in the beginning I was mainly mesmerized by that floating, drooping basset hound head. It was a while before I even heard the rest of the song, and then some greatest hits compilations, before poring through all the albums, music videos and interviews I could find. I couldn’t tell you why Enya, of all artists. At a time when I was increasingly losing friends to horoscopes, crystals, chakras and other infuriatingly New Agey realms, I wasn’t gung-ho for the witchy trend creeping into mainstream consciousness. I tried listening to other New Age, and mostly just found it grating. Maybe she was like a sonic smudge stick, with music so wildly unlike the primarily shouty, noisy bands I favored before that it was just what I needed to get me through a particularly difficult time. A therapeutic panacea for all the world’s problems, or at least my own.

But what is it that makes Enya so magical? I turned to Twitter, where my followers revealed that she was a conduit for their deepest, most private desires. One respondent compared her to “linen pants that you never have to iron,” while another cited “the layering of sometimes up to 80 Enyas.”A third enthused, “I just have a lot of respect for anyone who makes a global career out of humming,” which made me begin to foment a theory that Enya’s sorcery is linked to worldwide colony collapse: her power grows with every dead bee.

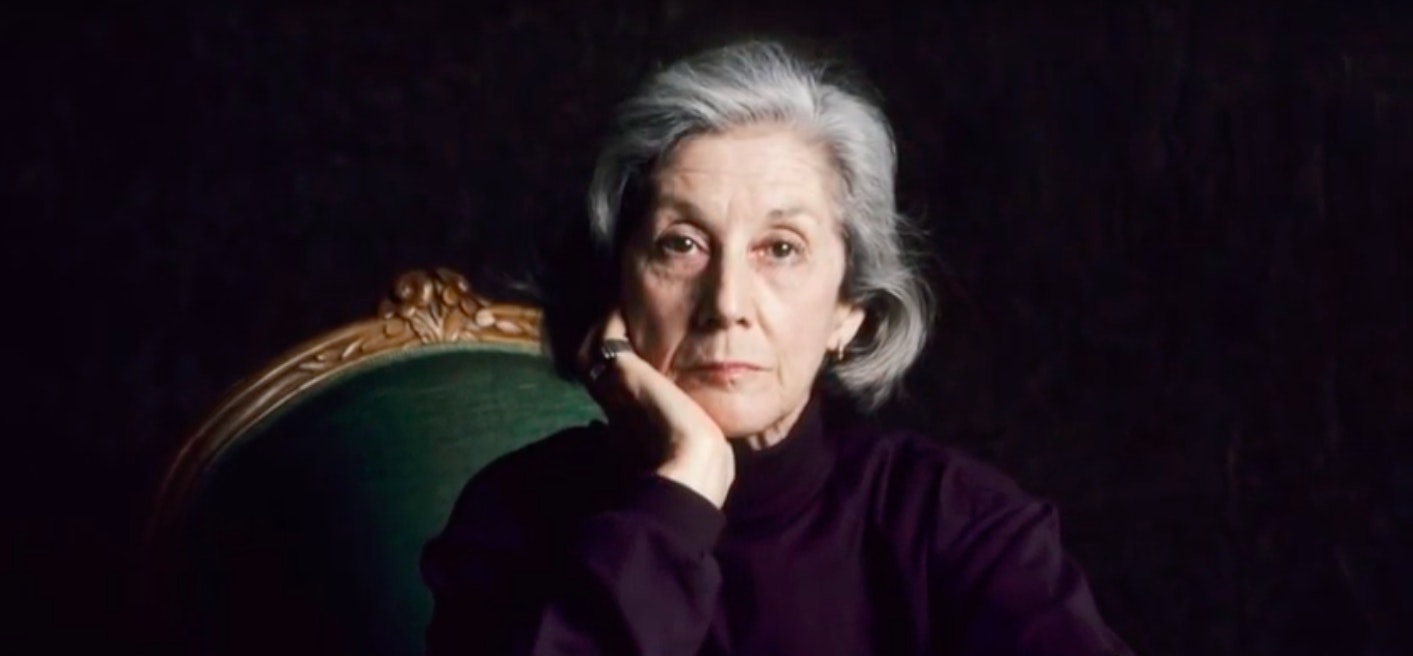

Let’s also mention her fortified Lalique crystal-filled seaside castle in Killeney, Ireland where she lives alone with her cats. It comes with a panic room. Bono is her nearest neighbor. She has a second home near Cannes, loves dance-themed reality tv, and would love to learn the Argentine tango. And while Enya’s music might figure into many people’s bedtime rituals, her own nightly winding-down is considerably more sumptuous. In 1992, she revealed to the Sunday Times that it includes a heated Japanese massage bed followed by a Jacuzzi, donning silken dressing gowns bought “while travelling in the East,” and writing in her diary. She’s no stranger to brands or luxury, but I imagine that her routine, once established, has remained unchanged to this day.

“She’s not exactly a barrel of laughs. You wouldn’t go for a few pints with her.”

Of course, Enya’s fiercely proud embrace of her Gaelic identity is also a favorite with people looking to reconnect with their Irish roots, however distant. Sales and streams spike each St. Patrick’s Day. There’s something so benign about her music that it uniquely allows white people to celebrate a white heritage with no danger of being perceived as closet nationalists. She can be shared this way, as she’s continued to disappear into herself. A 2016 feature in The Sun quoted her estranged uncle’s assessment of her as a “recluse” who had only been seen in public twice in the last decade. Enya alternately described herself as “dark and difficult.” An unnamed friend was quoted as saying “She’s not exactly a barrel of laughs. You wouldn’t go for a few pints with her.” This is super weird, the tabloid seemed to say, even as it inadvertently painted her lifestyle as The Dream.

Her embrace of immaculate privacy seems all the more remarkable in our current moment of data-driven hyperconnectivity. Intensely solitary by nature, her commitment to security increased after stalkers were able to break into her castle and even tie up one of her staff (because of course, Enya has staff). Online and in various distributed forms, we are so many refracted (and socially optimised) versions of ourselves, but Enya is always — and crucially, only — an accumulation of Enya.

Enya’s songwriting process similarly maps to an ecological scale: songwriting in winter, and arranging and fine tuning in spring and summer. It is unclear what she does in the fall. Since the beginning, she has worked with two longtime collaborators: producer and manager Nicky Ryan, and poet and lyricist Roma Ryan. (Her latest album Dark Sky Island arrived in 2015; though her U.S. sales have dropped, she remains steadily popular around the world.) I imagine their process to be not that dissimilar to those Miami cannibals, replete with the circle and ritualistic chanting but minus the long pig snack. Or perhaps her life is perfectly boring, a day in front of a computer then vegging down in front of her favorite show, Strictly Come Dancing. We don’t know, and never will.