Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

There’s a perspective-twisting lyric toward the end of 1930s blues singer Geeshie Wiley’s “Last Kind Words Blues” that always knocks me sideways: “The Mississippi River, you know it’s deep and wide / I can stand right here, see my face from the other side.” It’s a line that could be about so many things — the fragmented metaphysics of selfhood, the haunted presentness of the past, the ghosts of slavery. But lately it’s been reminding me of the polyglot musician Glenn Copeland at 75, listening back across the wide expanse of middle age to himself, singing from the other side.

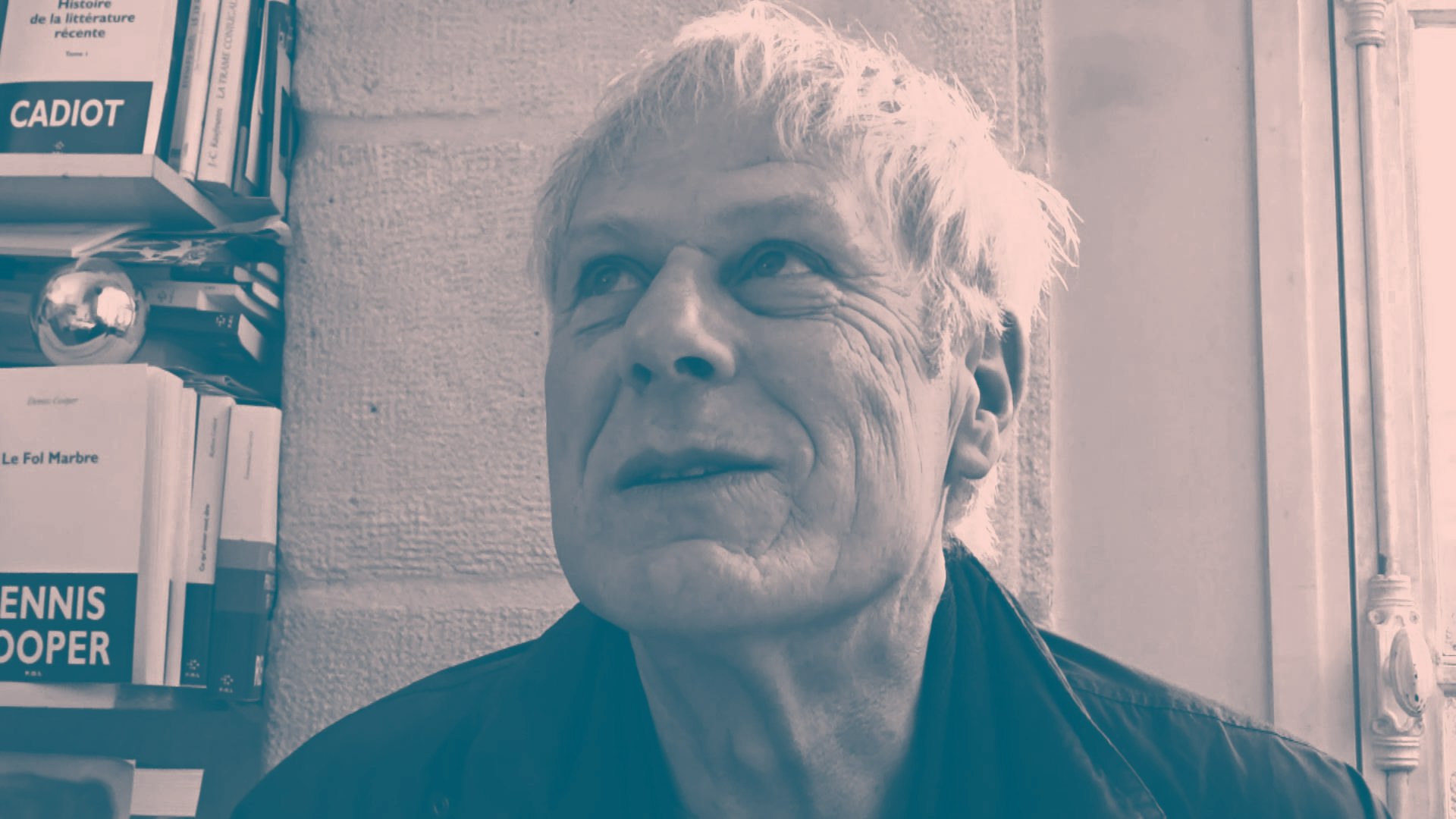

That Copeland now tours the world for thousands of fans is relatively astonishing; for most of his life, the world wasn’t ready for him. Growing up in post-war Philadelphia, he wanted to become a slapstick comedian and spend his free time scouring record stores for West African drumming and whatever Chinese imports he could find. But his parents pushed him to listen to big band jazz, and follow his father’s five hours daily practice of Chopin to train in classical piano and German lieder singing (which he performed at Montreal’s world’s fair in 1967, representing Canada).

Starting in the 1970s, he worked for nearly three decades as a comedic actor and musical contributor on Canada’s beloved children’s show Mr. Dressup, and later on Sesame Street and other similar shows. On his own time, he was making off-kilter music to far less attention, including two gnarled psych-folk albums filled with rollicking vocal performances and jazz-infused accompaniment, a bass-popping soul EP, as well as a new agey cassette of warm synth loops and drum-machine claps that unfold and swirl around his beautiful voice.

Back then almost no one was interested in his peculiar songs; for several decades he sold maybe a few hundred tapes and records. Eventually, he even stopped working on children’s television, where he felt out of time in his inability to live publicly as a transgender man. (He was born Beverly Glenn-Copeland, the name he still uses to release his music.) He continued working on music and grew old with his wife, happily but quietly in the solitude of rural New Brunswick.

Somehow, his synth-heavy Keyboard Fantasies, recorded in 1986, found its way to the ears of Ryota Masuko, a young Japanese collector who contacted Copeland in 2015 and purchased all the copies that had languished in storage for 30 years. Soon after, Copeland was barraged by record label representatives hungry to remaster and rerelease his long unappreciated and widely varied music. Keyboard Fantasies was reissued in 2017, followed soon after by his first two folkier albums, and most recently 2004’s Primal Prayer — which adds triumphant stacks of layered, cavernous vocals and danceable, syncopated percussion to the jazz, classical, and new age elements of his previous releases. His music was exposed to countless new fans, many of whom were born a half century after him.

When Copeland was a young musician, a palmist told him that his art would only be appreciated once he grew old, not that it made it any less jarring once it actually happened. “My telephone never rang for 50 years,” he told a Montreal audience in 2017. “Now it won’t stop ringing.” The millennials who eventually championed his music — “world citizens with a vision for protecting the Earth,” in his charitable estimation — had been predicted too, he said, though he’d stopped expecting them. “When there's a prophecy that something's coming,” he told me, “you think it's coming next week, right?”

The Earth notwithstanding, one thing millennials aren’t known for protecting are the rigid boundaries of genre that for years divided listeners, owing to the easy access and context collapse of the internet’s broken-but-endless ocean of music. With the proliferation of file-sharing services that began around the turn of the 21st century, the price of listening to something outside your wheelhouse dropped from $18.99 a CD to the cost of a click. An anarchic deluge of free blogs, forums, and playlists made music discovery more expedient and idiosyncratic, and shuffle settings on mp3 players further normalized the shoulder-rubbing of divergent sounds.

Still, perhaps some of the loss in genre-loyalty has been replaced by listeners’ attentive to mood. This is playlist mindset; we stan music for walking on a sunny day, dreamy vibes, sad bops, swagger songs, lofi hip hop beats to chill/study/relax to. “Chill music” especially, as Amanda Petrusich and others have observed, has proliferated as a tool for headphone-swaddled millennials seeking pleasant productivity in noisy coworking spaces and coffeeshops.

Simultaneously, YouTube’s recommendation algorithm has buoyed an already-ongoing critical reappraisal of new age and ambient music’s soothing sounds. Like legions of listeners with a YouTube tab open, SPIN writer Andy Cush found himself reliably served a relatively esoteric 1986 album by ambient musician Hiroshi Yoshimura, regardless of what he had been playing beforehand. YouTube knows we are unlikely to turn off such pretty, unobtrusive music once it’s going, and it’s within the context of this generational yearning for tranquility and mechanically-induced open-heartedness that Copeland’s own 1986 album of contemplative synths was disinterred from the depths of obscurity. “Your album is like a symbol for the younger generation as we rediscover this kind of music,” Ryota Masuko told Copeland, when the two finally met this year. (Masuko, for what it’s worth, discovered Copeland’s music after an old cassette was passed to him.)

In 1957, a spiritual awakening helped John Coltrane kick heroin after nearly a decade of grueling addiction, and in turn transformed him into a musical zealot. For the remaining decade of his life, he played with a searching devotion, seeking to redefine the harmonic and spiritual possibilities of jazz. He recorded and performed almost nonstop in apparent penance for all his wasted time, trying to make more of what he had left than should have been possible. “The speed with which he transformed his music has been attributed to his recognition that the years of drugs and drink wounded him irrevocably, that he was living on borrowed time and in much pain,” the critic Gary Giddins wrote.

I find this thread of Coltrane’s life very moving. Who among us has not woken up one morning (or afternoon) and self-flagellated over the evaporated possibilities of a weekend, a month, a decade — so much time wasted, and for what? His response, though beautiful, is not so relatable. Such realizations, for me, tend to beget self-pity and even more procrastination, not ascension nor Ascension.

“I'm a Buddhist. So I believe you come endless times around, you're constantly born — not necessarily here, but somewhere.”

Which is why Copeland’s reaction to the widespread discovery of his wonderful music this late in his life is to me so refreshing and understandable. Perhaps in no particular need of a spiritual awakening after decades of practicing Soka Gakkai Buddhism, he didn’t appear particularly concerned with rectifying years of unjust disregard for his music. Instead, in interviews, he mostly seemed perplexed about the turn of events — verging on a little flustered at repeated interrogations of recordings he’d made three decades earlier. “It freaks me out. Because I’m so removed from that, it’s taken me a while to reconcile the sound that I hear,” he told a moderator when asked how he felt listening back to one of his recordings from the early 1970s. “So it’s like I hear that and it’s like do I relate to that? No, not really.”

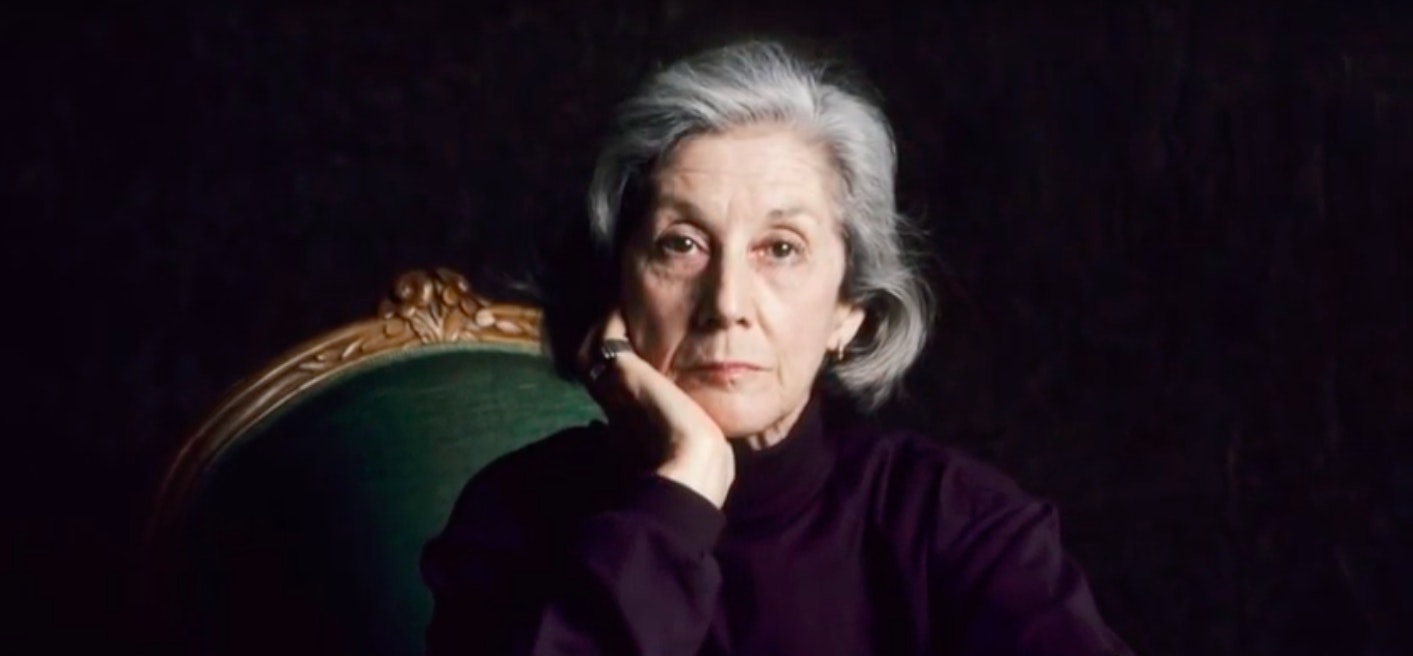

And wouldn’t you be? Imagine being asked to account for the remains of the person you were so many selves ago. (Sometimes, by the time a friend responds to a text I’d sent earlier in the day, the former me who sent the message already feels embarrassingly alien.) In Toni Morrison's Jazz, the pitiable Joe can remember the actions of his past self, but he’s completely lost touch with the why: “He recalls dates, of course, events, purchases, activity, even scenes. But he has a tough time trying to catch what it felt like.”

Even beyond the stylistic changes across his career, Copeland’s music often explicitly grapples with this kind of fluidity of the self. “Welcome to you both young and old,” he sings reassuringly over gurgling keys on the opening track of Keyboard Fantasies. “We are ever new.” It’s a fitting attitude for someone whose religious beliefs confound traditional Western ideas about finitude and fixedness of identity. “I'm a Buddhist,” he told me. “So I believe you come endless times around, you're constantly born — not necessarily here, but somewhere.”

Although Copeland sold a few fistfuls of his tapes before rediscovery, his stark shifts in sound largely took place in private, outside of the machinery of commerce, audience expectations, and the opinions of critics. His songs have the outsider appeal of what French artist Jean Dubuffet called art brut: “Those works created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses – where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere.”

Plenty of popular artists have continued to evolve dramatically throughout very public careers — Miles Davis, Joni Mitchell, and Scott Walker, to name a few — and even more have basically remade the same record for decades. In all of these cases, it’s impossible to disentangle the artist and work from their social context. Art made for public consumption isn’t necessarily inauthentic; much of my favorite music is sung directly into the discourse, a call and response with the world around it. Upending artistic expectations can result in astonishing innovations in sound, and even commercial incentives can help a band figure out what they’re best at. But I’m sometimes left to wonder what might have transpired in a different context.

The work of other outsider artists like Copeland pulls back the curtain in service of larger questions about contingency of self: Who are we when we think no one is looking or listening? Art from outside the system can help us to better understand its effects on those working within it, even if the “pure and authentic creative impulses” Dubuffet praises are ultimately a fantasy. Even in private, we are performing.

Copeland’s music also underscores how often the performance of our various identities manifests in unique and complex ways — gender, for example. Though he’s been openly living as a man since the early 2000s, he still sings in a high-flying contralto and mezzo-soprano voice that’s only lost a few notes of the three-octave pyrotechnics he once commanded. “I would have loved to be able to present myself in a totally exteriorly masculine way in the world. However, to do that would’ve been to mess with the gift I was given,” he said. Laura Jane Grace and Anohni, both of whom also came out as transgender after lengthy singing careers, made similar decisions to continue singing with roughly the same voice they always had. And all performers — cis, trans, or otherwise — have their own blend of masculine and feminine qualities; such are the dynamics of personhood. “Are you going to say that because you function primarily as a male in society, does that mean that you have no feminine energy in you?” Copeland said. “I don't see those things as in conflict, I see them as subtleties.”

On “Back to Bachland,” the otherworldly second track on Primal Prayer, the song’s apocalyptically orchestral synths are matched by a team of windswept Copeland voices: one pitched down to a hurricane’s baritone, while its higher twin shadows the melody in unison an octave up. After a few rounds, yet another Copeland voice joins the throng with a faster-moving counterline. The layering continues with the addition of two more Copeland vocal tracks, each with its own spectral melody and cadence. “In the passing of time, you come to know your being,” one of the Copelands sings as an overwhelming multiplicity of selves orbit as one. “In the cradle of time comes another day.” Subtleties, more subtleties — a voice hearing itself from the other side.