Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

Between calls to mindfulness, TED Talks, self-help lit, and the rise of hashtags like #riseandgrind and #blessed, the cult of positive thinking has effectively infiltrated mainstream culture. It tells us that if we can simply scrub all nasty thoughts from our minds, scrawl an affirmation onto the mirror, and take a 10-minute superhero power stance, we will attain the happiness we seek — nay, deserve. That’s nice in theory, but this kind of thinking makes me eye-roll like a Kardashian at her most dismissive. Ignoring negativity altogether feels a bit like cleaning your house by stuffing every visible mess into a cupboard or drawer. You haven’t dealt with the problem; you’ve tucked it away, ready to spill out later. And more importantly, you’ve ignored one of life’s cardinal rules: The light doesn’t exist without the dark, and sometimes you’ve got to get a little sad to get a little happy.

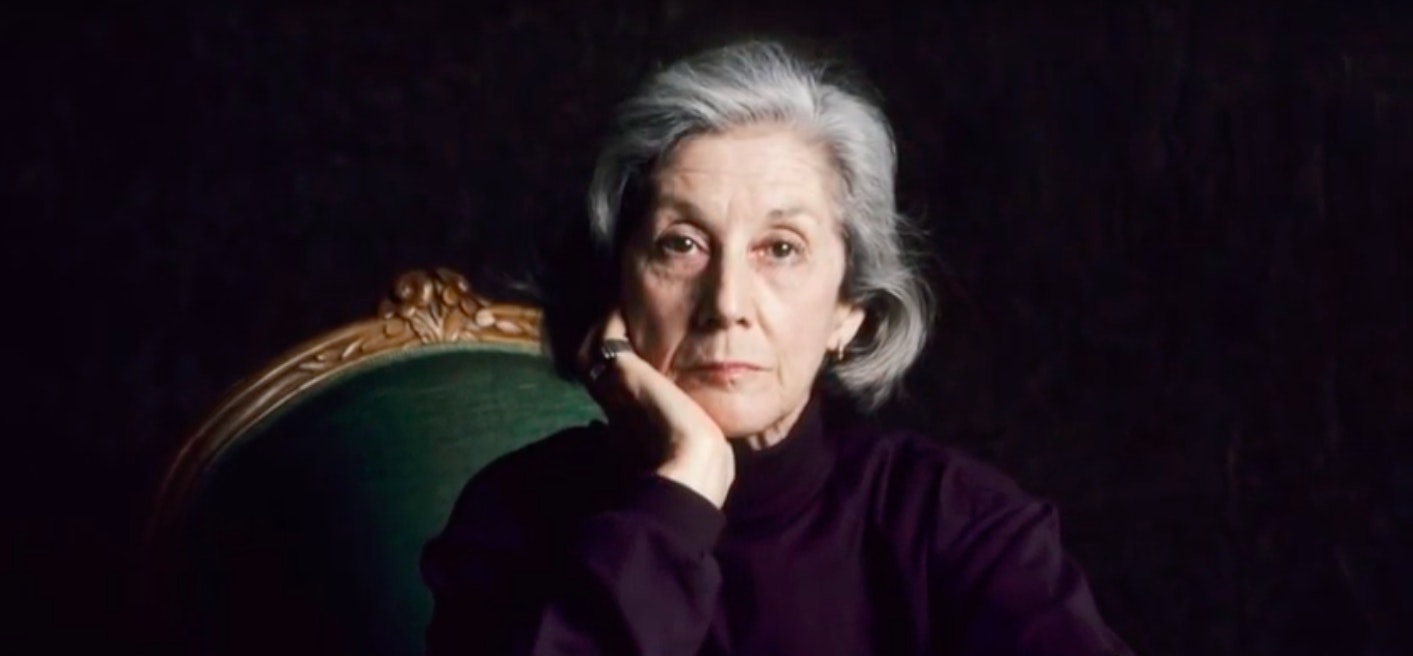

If anyone knows this dichotomy, it’s Yoko Ono. Follow Ono on Twitter and you’ll be #blessed with near-daily directives in positive thinking — koans like like “Analyse less. Enjoy more” and “Reignite the glimmer in yourself.” While it’s nice to see such optimism on a website used mostly to soft sell white nationalism, Ono’s prompts of metaphysical and imaginative self-love carry more weight than their mindful counterparts, because each one is preceded by Ono’s 50-year history as an avant-garde artist with a penchant for the positive and, more importantly, as one of popular culture’s most villainized women. Few names in modern history connote such a pervasive reputation as hers. The way names of doctors come to describe diseases, Ono’s name has come to describe, irrevocably, the cardinal sin of a woman breaking up the bros. Reference her in a certain kind of circle, and you’ll enter a fraternity of euphemistic mutual understanding that Ono had — as many women do not — no worth outside her role as a more notable man’s wife.

The official record is a little different. Before she and Lennon met, Ono had already made important contributions to the fields of conceptual and performance art, one of which made Lennon fall in love with her: In 1966, the Beatle visited a London gallery displaying a ladder, above which hung a magnifying glass. Lennon climbed the ladder, put the glass to the ceiling and read the tiny but consequential word written above: “Yes.” This piece is perhaps a perfect distillation of Ono’s overall artistic vision: Concerned with the imaginative mind, Ono’s work pushes viewers to see the world slightly askew, and to engage with that vantage point in a playful way. Her “instruction paintings,” which are not paintings but short conceptual poems that prompt readers into various intellectual — and impossible — acts (“Get a telephone that only echoes back your voice. Call every day and talk about many things.”) are reminiscent of her whimsical Twitter presence, which illuminates her unswerving artistic vision over the course of 50 years and disparate mediums.

Many these instruction paintings, collected in her 1964 book Grapefruit, also showcase her penchant for positivity, but much of her work has commented on humanity’s shadowed side, too. The famous “Cut Piece,” also from 1964, featured Ono sitting alone on a stage, dressed in a suit with a pair of scissors in front of her. The audience was instructed to cut bits of her clothing off of her body, one by one, an act that quickly turned violent. Her film, “Rape,” for which Ono hired four male filmographers to stalk and film a young woman without her permission, replicates the violence of the incessant male gaze. In the course of the 75-minute film, we see the girl go from being flattered by their attention to genuinely freaked out, eventually unraveling in exhaustion.

I am very fortunate to feel so much love for almost everything. I don't know why that happened. Probably because I know the other side of life… very sad, very dangerous, and very painful.

— Yoko Ono (@yokoono) December 23, 2017

All of this was made before she met Lennon — or, in the case of “Rape,” in conjunction with Lennon—but the years after his death have been extremely prolific for her, too. She’s released nine albums since 1981, and has had six songs top the dance charts. She’s produced permanent installations for museums and public spaces. She’s collaborated with contemporary bands, has had retrospectives at major museums, and has been given prestigious awards. Just this year, she was one of 50 artists asked to create a cover for New York’s 50th anniversary. (Her design was all white with the phrase “Whisper to me” placed in the middle in small, simple text). She constantly has shows opening in galleries across the world and continues to create accessible bits of whimsy like Grow Love With Me — a series of $30 recycled cans full of dirt and “magic beans” that grow the word “Love.” And this spring, Ono will be the voice of a character in Wes Anderson’s upcoming film, Isle of Dogs.

Throughout all of this, her work, her ideas, and her endurance have been eclipsed by her reputation. Despite awards and hits and homages from influential people, her name is still synonymous with an ugly myth. This is exceptionally brutal because, even beyond the harshness of her cultural treatment, Ono’s history is shaded with darkness. She was born in Japan and after World War II, she and her family were reduced to begging for food on the streets. She attempted suicide in 1962 and was subsequently admitted to the psych ward. She had two failed marriages before Lennon and one child, Kyoko, who, after her divorce, was kidnapped by her ex-husband, raised in an apocalyptic Christian cult, and kept from Ono for 27 years. With Lennon, she suffered three miscarriages, which caused her to be on bedrest while she was pregnant with their son, Sean. Then, in 1980, her husband was shot and killed in front of her. After all that, she was ostracized and villainized for decades.

In spite of this, Ono has maintained some kind of fairy godmother-level positivity — possibly because her survival depended on it. “I finally came to the conclusion to use that big energy of hatred that was coming to me and turn it around into love,” she said in a 2013 interview. In the same vein, she recently tweeted: “I am very fortunate to feel so much love for almost everything. I don't know why that happened. Probably because I know the other side of life… very sad, very dangerous, and very painful.” Over and over, Ono stood up to brush off her critics, opting instead to douse them in love.

In the present moment, optimism can feel like a useless emotion considering the sobering reality of what’s going on; the rise of the cult of positive thinking feels like a direct response. But while that particular brand of cheeriness easily shades to naivete in the face of, say, the threat of an ego-fueled nuclear war, Ono’s seems particularly clear-headed. Even her most positive messages maintain a balance of light and dark, an acknowledgment that something has been broken that needs to be fixed. By being intimately acquainted with the shadowed side of life, Ono is able to offer a style of positivity — a singular focus on condemnation of hate and war through love and peace — freshly relevant to our depressed national temperament.

In a few weeks, Ono will open a new show at the Gardiner Museum in Toronto. One of her works, titled Mend Piece, is made up of fragments of broken ceramic cups and saucers strewn across a table, which visitors are invited to reassemble using glue, string, and tape. “As you mend the cup,” Ono says, “mending that is needed elsewhere in the Universe gets done as well. Be aware of it as you mend.” After restoration, visitors are invited to place the cups on shelves in the all-white room, rendering what was fragmented newly exceptional, a broken thing mended for all to see.

(Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the location of the Gardiner Museum.)