Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

I grew up in a Catholic family and attended Catholic school. As a kid I knew that Jesus died for me like I knew the Earth was round. It was so clearly true that my belief didn’t require anything like faith; God in all his complexity was a subject that could be mastered like any other. But then I learned other religions existed — that Catholicism was just one item on the menu — and doubt blossomed overnight. Soon I was a teenage apostate, ready to take a swing at anyone who seemed content in their ridiculous beliefs. I refused to be confirmed in the faith, got into existentialism, argued with my teachers, wept to my childhood priest in guilt and confusion. By the time I left for college, I never wanted to see the inside of another church. I hated religion and resented the religious, with one critical exception: I loved Sufjan Stevens.

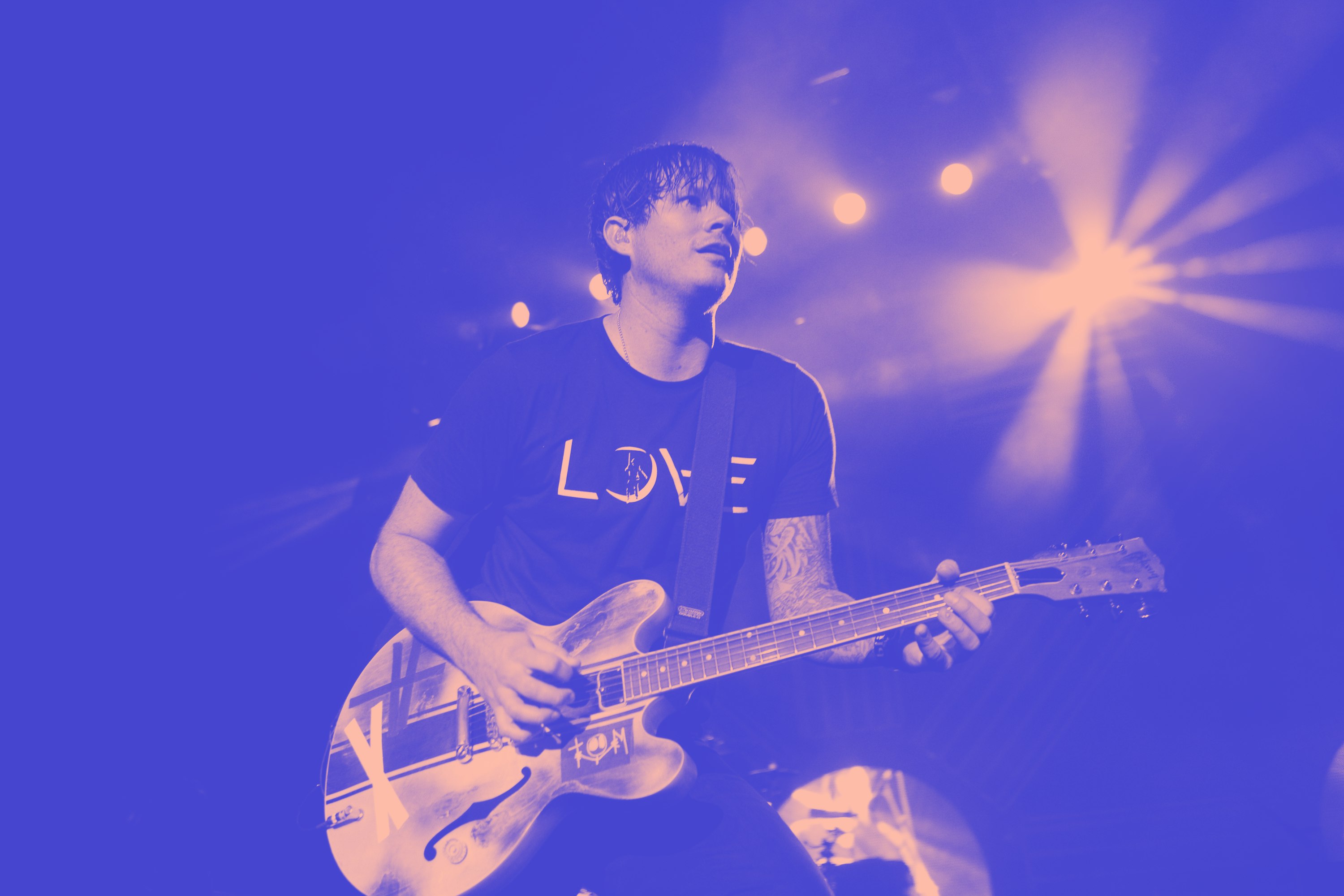

When I was 15, I bought Sufjan’s 2004 album Seven Swans at my favorite record store. Seven Swans is an indie folk album that includes tracks about the biblical Abraham, the apocalypse, and the transfiguration of Jesus — in a review, SPIN said it sounded “like Elliott Smith after ten years of Sunday school.” But I didn’t realize any of this until I got home and fired up my Discman. I’d purchased the album because it had a nice illustrated swan on the cover, and the record store staff, who I revered, had placed it on their display of best new music. It didn’t occur to me that I might be picking up a piece of Christian apologia — in my young mind, there was a strict divide between religious and nonreligious spaces, and Easy Street Records was a shining secular stronghold.

As I listened, I remember feeling appalled and somehow tricked, like I had been scammed out of a precious $14. Then I realized I loved it. I played Seven Swans on loop for months, though I was increasingly troubled by its hold over me. How could a song about Jesus chatting with God on a mountaintop make me well up with tears, when the same story read in church left me cold? Did I just really love the banjo? I was tempted to chalk up Sufjan’s Bible stories to a sort of folksy posturing. If I loved his music, I thought, his Christianity couldn’t be sincere.

In interviews, Sufjan made sure to distance himself from Christian music as a genre. “On an aesthetic level, faith and art are a dangerous match,” he told a blog called Delusions of Adequacy in 2006. “Today, they can quickly lead to devotional artifice or didactic crap. This would summarize the Christian publishing world or the Christian music industry.” But he was never coy about his faith, which really was sincere, and which permeated his life and art. I read the interviews and puzzled over them. Then I pirated his Christmas albums, even as I schemed to avoid Christmas mass.

I’m hardly unique in my defection from the church. Millennials are the least faithful generation in American history — the only religious practice growing in America is no practice at all. But Sufjan has a broad appeal among my increasingly agnostic peers, which I suspect has something to do with the complexity of his faith. If you’re used to a religious practice that demands submission and compliance, Sufjan’s approach is thrilling, and liberating. And if you have only a glancing familiarity with Christianity, I imagine this is a more interesting access point than those smash hits about Jesus taking the wheel.

In Seven Swans, Sufjan sang about God commanding Abraham to sacrifice his young son, with a sparse musical arrangement that made the retelling solemn and disquieting, far from a celebration of obedience. He described the apocalypse as foretold by the Book of Revelation: trees burn, a dragon appears, the singer’s father “turns into coal.” There was no comforting vision of heaven, only complete annihilation at the hands of the Lord. In Illinois, he sang cheerfully about the impossibility of being a stepmother, a child’s discovery of his father’s affair, a serial killer, the divine beauty of a UFO sighting, and an altered relationship with God after the death of a young friend (“He takes, and He takes, and He takes.”). Here were tales of Christianity and secular life that mirrored one another, and reflected my own experiences. They were full of raw wonder at the very fact of existence, but also bewildering, riddled with pointless violence and contradiction, shot through with human failure.

“Money and power and governments are fraudulent and false gods. We must be in the world, not of the world.”

Anyone who has lost a belief system knows how strange and isolating it can be. One day you feel sure-footed and surrounded by community, guided by moral principles that seem objective — a comfort, even as you constantly disobey them. And then it’s gone. You have no idea what it might mean to do the right thing, and you sense for the first time that you’re profoundly alone. Sufjan’s songs didn’t bring me back to Christianity, but they did give me a version that felt honest, one I could accept and live alongside. Later I would find similar solace in Simone Weil, Marilynne Robinson, Teilhard de Chardin, and a long line of liberation theologists. But I found Sufjan first.

In the last few years, it’s felt increasingly difficult to know how to live. Even if you’re sure of your politics, it’s a daily struggle to avoid the hardening of your own heart — a casual skim of the news means opening yourself to a barrage of horrors. I’ve been turning to Sufjan’s 2015 album Carrie & Lowell, and 2017’s The Greatest Gift, a collection of Carrie & Lowell outtakes and remixes. Both center around the death of Sufjan’s mother, a woman who dealt with mental illness and addiction, and left Sufjan and his siblings to be raised by their father and grandparents when they were very young.

These are clearly songs by an older person, full of regret and longing, hyper aware of mortality. “What's left is only bittersweet,” Sufjan sings on “Eugene.” “For the rest of my life / admitting the best is behind me.” “We’re all gonna die,” he sings over and over on “The Fourth of July,” a song that describes the end of his mother’s life. I get that line stuck in my head, unbidden, when I read about the atrocities of the day. In a way, it’s another apocalypse song. These albums are intimate and specific, but somehow function as the perfect soundtrack for our era of failure and collapse.

They are also songs of forgiveness, an attempt to understand the mother he barely knew. “I say make amends while you can,” he told Pitchfork in 2015. “Take every opportunity to reconcile with those you love or those who've hurt you.” In writing about his mother’s death, he said he was “in pursuit of meaning, of justice, of reconciliation. It wasn't very fun.” Still, what choice did he have?

What choice do we have? On very bad days, I listen to “The Greatest Gift” on loop. “The greatest gift of all,” Sufjan sings, “and the law above all laws / is to love your friends and lovers / to lay down your life for your brother.” It’s the biblical “love your neighbor as yourself,” but presented not only as a commandment, but as a profound joy — a fundamental responsibility that is also an opportunity for redemption and grace.

I no longer struggle with my loss of faith; I’ve found other value systems that help me orient myself in the world, and I can access the divine by seeing friends, or going to the beach. Being without some formal religious practice isn’t as different as I thought it might be—at the core of every way of living, there’s a kernel of something we can’t fully understand. I came to accept that no one is fully rational. We’re a necessarily faith-based species.

A few times since Trump’s election, Sufjan has addressed America in mini Tumblr sermons that represent Christianity’s best and most radical facets — the parts I ultimately decided to keep. “You must love your enemies, serve the poor, give everything away, and put yourself last,” he writes. “This goes against everything the world has taught you, and it goes against your instinct, and it most certainly goes against the laws of free enterprise and corporate interest. Money and power and governments are fraudulent and false gods. We must be in the world, not of the world.”

This isn’t empty virtue signaling. It’s an invitation to carry on with hope and love in a world that calls for nihilism and despair. Sufjan is asking the impossible, of course; to attempt a perfect love is to fail, again and again. But it’s also the greatest gift we can give — to others, and ourselves.