Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

Last weekend, I went around at the University of Memphis English Department party compulsively asking everyone variations on “So do you like Alanis Morissette or what?” (“Have you listened to Alanis Morissette recently?” “Are you an Alanis fan?” “You’re Canadian, do you like Alanis?”) All of the answers I got were variations on “No.” Some of my colleagues (the Canadians) told me that they remembered her as a child star, back when she made dance music that sounded like a mix of Paula Abdul and Pat Benatar. I have yet to find anyone in my real life who regards her with anything other than fond ‘90s nostalgia, that curse of the CD binder.

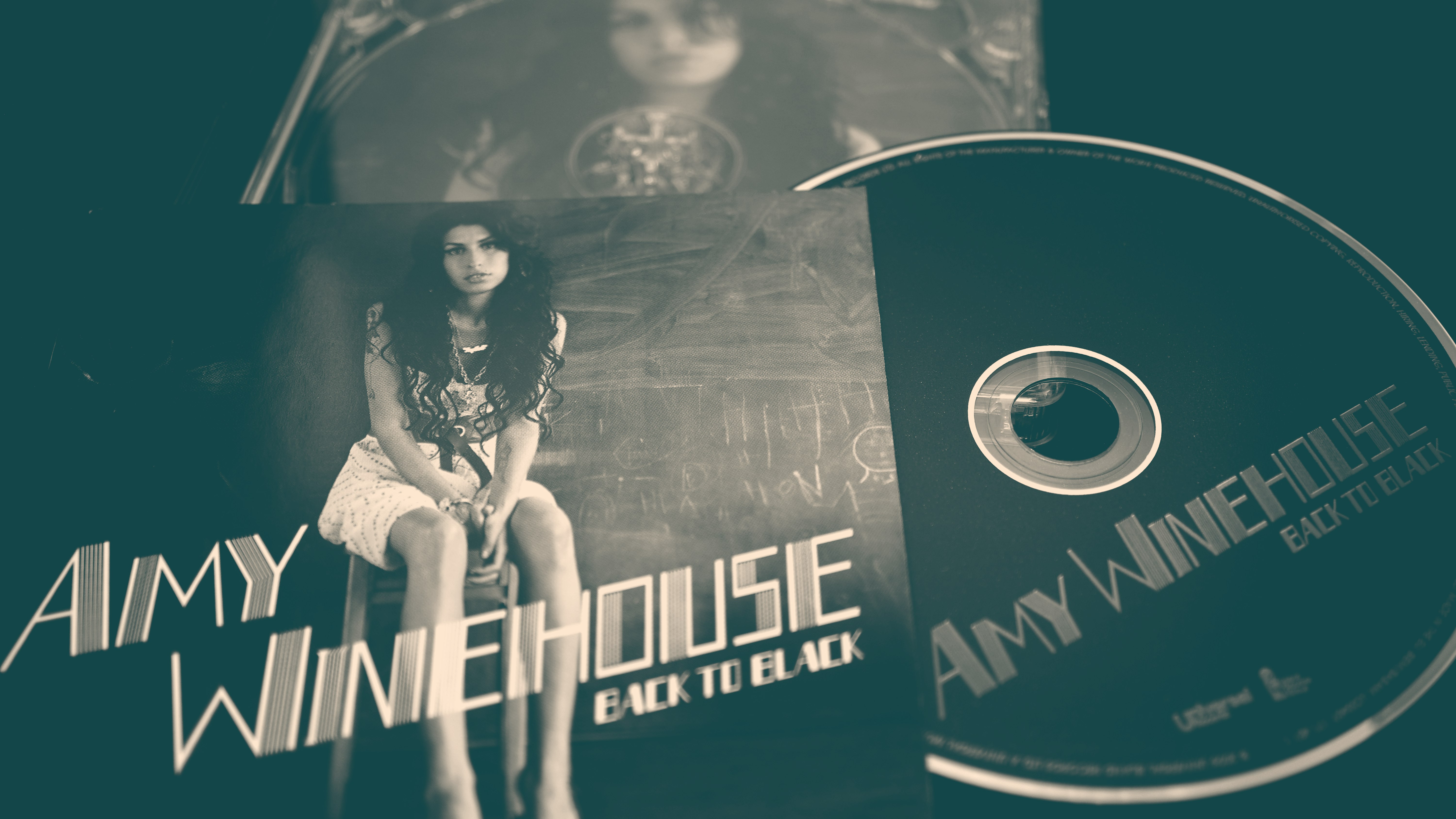

I was once like these people. I thought of Alanis as catchy, corny, and second-rate — and, after all, she was no Fiona Apple. My Alanis conversion occurred while driving from Boston to Tennessee to start this new professor job. My boyfriend and I downloaded the Spotify Landmark sessions about Jagged Little Pill, released on the album’s 20th anniversary in 2015. In it, Morissette and her co-writer and producer Glen Ballard describe the process of making the album. They are a little too in love with the songs they wrote together, and Glen is a little too in love with Alanis. (“Five months after we wrote this,” Ballard says about “All I Really Want,” “She would emerge as one of the most charismatic and powerful women on the planet.”) But they also describe their lovely and organic collaboration, as they wrote songs and created demos often in a matter of hours or minutes. Morissette would quickly scribble lyrics in a notebook or else improvise them over Ballard’s instrumentation. This is to blame for some of the songs’ triteness (as she so cogently puts in on “You Learn,” “You live / You learn / You love / You learn”), but it’s also why Jagged Little Pill still sounds so fresh and undone and interesting today.

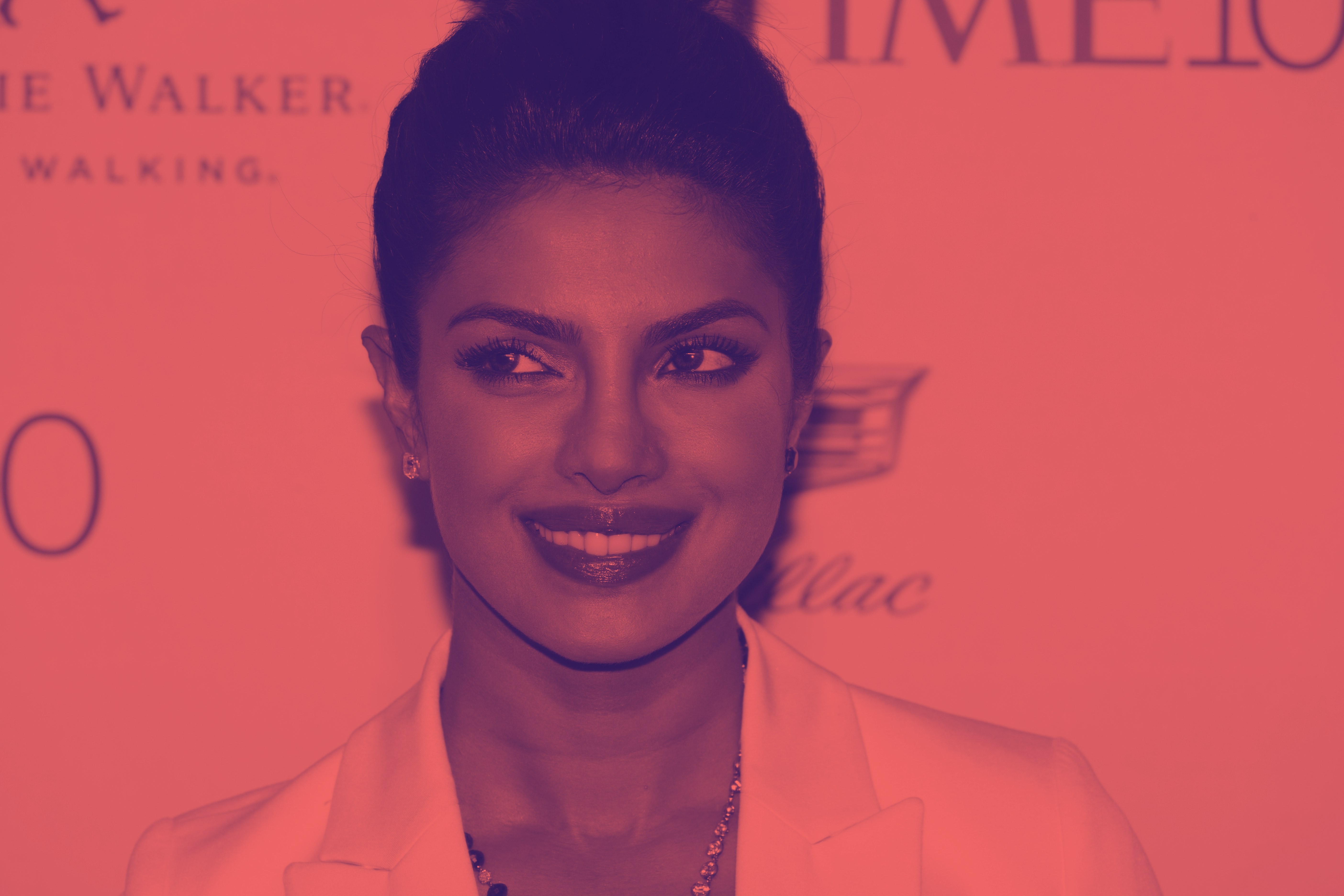

Morissette made the album in 1994 in a burst of freedom, after being dropped by her Canadian record label because she wanted to write more of her own music. It is beautiful to hear her tell the story of how, at only 19, she regained power over her image, after years of being exploited as a teen pop sensation. This narrative was mostly missing from initial coverage of Jagged Little Pill and its lead single “You Oughta Know,” with journalists treating her, infuriatingly, as just another teen pop sensation, even if she was one who scared them a little. Rediscovering annoying reviews of great female artists by creepy male rock critics is old hat by now, but even positive reviews of Jagged Little Pill were condescending. Robert Christgau wrote that Alanis was “happy to help 15 million girls of many ages stick a basic feminist truth in our faces: privileged phonies have identity problems too.” I don’t even know what that means, but the general impression was that she was the ideal studio-molded anti-pop star: a snarling Veronica, not a perky Betty.

This contradictory distrust in both Morissette’s bald emotion and her unexplainable polish drove the discourse surrounding her, and she was treated with the dismissive respect reserved for anyone who gets a diamond album singing only for women and girls. The jokes about her as an angry ex-girlfriend got old, as they later would with Taylor Swift. Somehow, it’s still trendy to rag on her for misusing the word “ironic” on her most successful single, though it is a subtler and smarter song than it sounds like at first listen. As Alanis grinningly sings, “Isn’t it ironic, don’t you think,” she perfectly evokes the Jerry Seinfeld and Chandler Bing school of “irony,” beloved by the men who list sarcasm as an interest on their OkCupid bios. “I’ve had my ass kicked for 20 years about it,” Morissette says goodnaturedly about “Ironic” on the Spotify tapes. “I think people had a lot of issues with perhaps my ‘stupidity,’ or Glen’s and my lack of caring for being perfect… For us it was just making each other laugh that whole song.”

It does seem unfair all the shit Alanis has gotten for “Ironic,” especially considering that stupidity is one of the chief pleasures of rock music, though it’s often billed as simplicity, frankness, rawness, or vulnerability. One of the masterpieces of the pop form goes “Be my little baby (be my, be my)” over and over; garage and grunge rockers have always achieved transcendence by playing it as stupid as possible. I don’t know why Alanis is so rarely compared to her fellow genre-mashing weirdo Beck, who also blended folk songs with sampling, and whose nonsensical first hit single is about being a loser who should be killed.

I mean, I do know why. There is an expectation of earnestness from women artists, as if we are not conscious actors but banshees wailing our allotted portion of eternal pain. We are, ironically, allowed no irony. And even as critics misunderstood the subtler meanings in their songs, the entire Lilith Fair crowd of singer-songwriters was dismissed as being too serious, too earnest, too political, a total buzzkill. But the ability to write seriously was exactly what Morissette was seeking when she came to the U.S.; after she and Ballard wrote “Ironic,” she decided that she would write the lyrics alone for the rest of the album, in order to push herself to write more honestly and autobiographically.

This is what critics really misunderstood about Jagged Little Pill: she was writing in earnest, but about much more than breakups. In their review of Jagged Little Pill, Entertainment Weekly wrote that “in [Morissette’s] songs, men take her for granted and mentally abuse her, and she retaliates by threatening to leave one of her exes’ names off her album credits (talk about a career-minded individual).” But the abuse she suffered at the hands of men in the Canadian record industry was serious and pervasive — she was a vulnerable child, not a woman scorned. The song EW is referring to, “Right Through You,” is a breathtaking “fuck you” to the creeps who once were in charge of her career, as she sings, “You took me for a joke / You took me for a child / You took a long hard look at my ass / And then played golf for awhile.”

There is an expectation of earnestness from women artists, as if we are not conscious actors but banshees wailing our allotted portion of eternal pain. We are, ironically, allowed no irony.

Morissette has spent her entire career calling out the egregious and mundane harm men perpetrate on young women. Her late hit “Hands Clean,” which describes a relationship she had with an older man as a fourteen-year-old, is brilliant and sad in its depiction of his manipulation: “If it weren't for your maturity none of this would have happened...” Morissette sings to herself in the voice of her lover. “If it weren't for my attention you wouldn't have been successful/And if it weren't for me you would never have amounted to very much.” Her signature song, “You Oughta Know,” in which she beats down her ex’s door and forces him to confront her in all her rage, takes on a different tone when one remembers that a teenaged Alanis wrote it about a man 17 years her senior. The miraculous thing about Jagged Little Pill is that Morissette transformed these experiences of being harassed, assaulted, underestimated, and dismissed into something no one could dismiss, a record so big it took over the world. She did it fearlessly, undeterred by the risk of becoming that dreaded thing, an angry brunette. “A lot of people have asked me why I was so angry then,” Alanis says with a laugh on Spotify Landmark, “Implying that I’m no longer angry.”

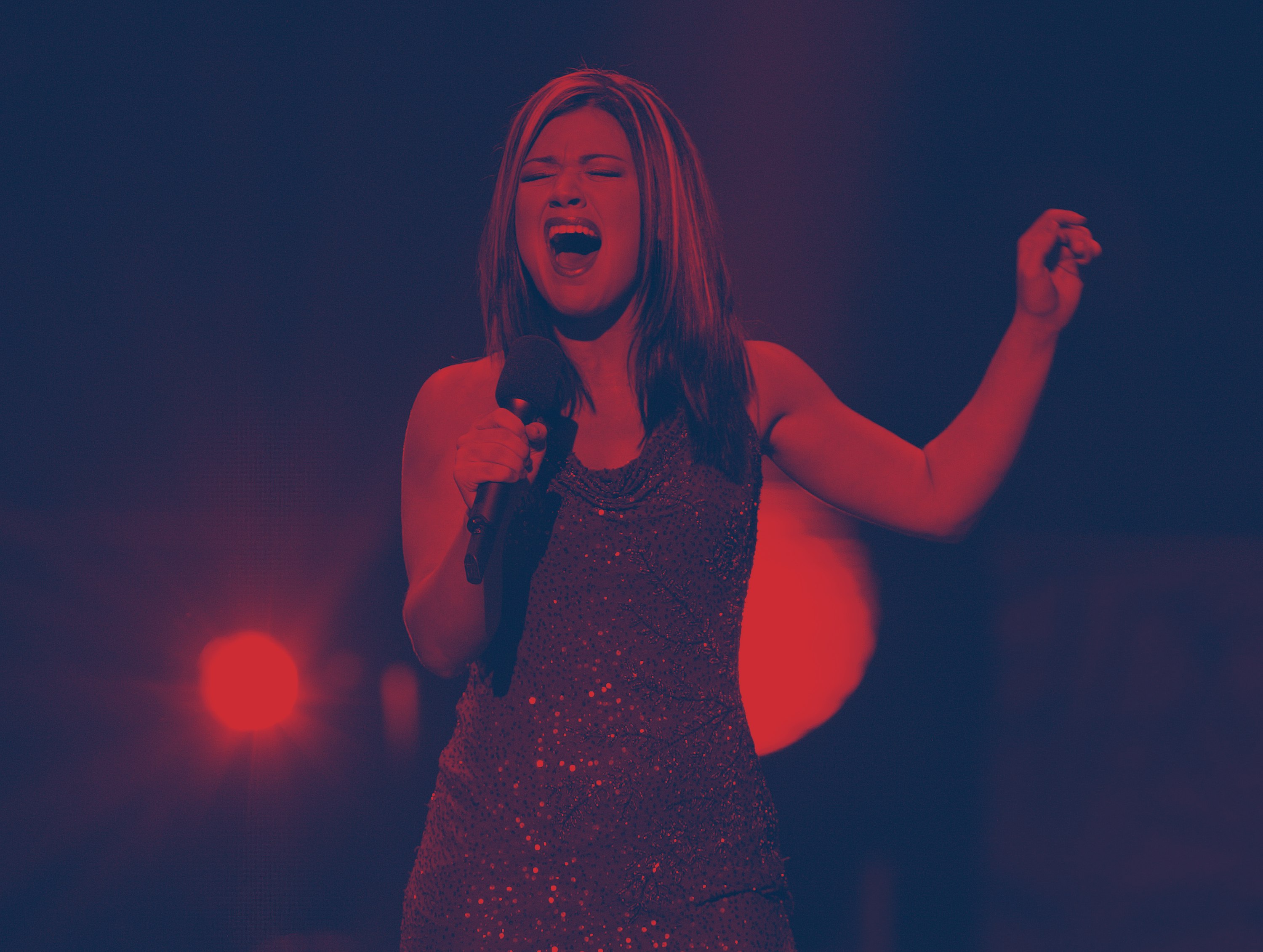

Morissette continued to evolve after Jagged Little Pill. Her second album, Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie, is good too, with lyrics that are more wordy and clever than deadly earnest. But Jagged Little Pill is still arresting, mostly because of the range and flexibility and control in Morissette’s vocals. Morissette recorded all of the album’s vocal tracks in one or two takes, usually on the day the song was written, and every vocal track on the finished album is a demo. This is an insane feat considering how she trills and growls and screams, belts and yodels and whispers, often on the same track. In live recordings Morissette often sings lilting alternate melodies for her most famous songs, which already have some of the most strange and haunting melodies ever heard on the radio. (For my money, the only contemporary artist who matches Morissette’s note-perfect plasticity is Beyoncé, whose album Lemonade is as much a demonstration of her ability to sing in every genre as anything else, and who executed the only successful cover of “You Oughta Know.”)

Driving through the Blue Ridge Mountains on my move to Memphis, the Alanis revelation hit me like a bolt of blinding light. It happened when we listened to “Perfect,” in which Morissette crescendos in both volume and emotion from a soft soprano to a Janis Joplin wail. It turns out the demo for this song was what Morissette and Ballard used to pitch record executives — which makes sense to me, because as we listened I turned to my boyfriend and blurted out, “If you found a teenager who could sing like that, wouldn’t you try to exploit her?” That’s what inspires me about Morissette, in the end. When she was remarkably young, she recognized her voice for the goldmine it was, and decided that she would be in charge of how it was used.